|

After her son, Shane, was diagnosed with a congenital diaphragmatic hernia, Dawn Williamson formed the charity CHERUBS as a way to offer education and support.

photo: Lynn Cañez, 3rd Floor Studio |

Guardian angels

One baby’s congenital defect leads to a nationwide support group

by Kelly Maicon

It was late January in 1993, and just like any new mom-to-be, Dawn Williamson was excited and anxious to meet the baby growing inside of her. But during her pregnancy, Williamson had these haunting nightmares that there was something wrong with her baby.

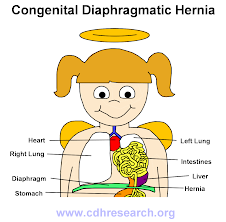

After almost 10 hours of labor, a baby boy named Shane arrived. But Williamson’s joy immediately shifted to dread as she saw her nightmare become her reality: Upon cutting the umbilical cord, her baby turned blue. Shane was born with a left-sided congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) and multiple other birth defects.

CDH affects approximately one in every 2,500 babies, or about 1,600 babies in the United States each year — and between 35 and 40 annually in North Carolina. To put it into perspective, it occurs about as often as cystic fibrosis and spina bifida.

Sadly, half of all CDH-diagnosed babies do not survive. Some survivors end up suffering through life with lasting health problems such as feeding aversions, gastrointestinal problems, asthma, allergies, scoliosis, pulmonary hypertension or other long-term pulmonary problems.

On a mission

What Williamson expected to be a short hospital stay in the maternity ward turned into relocating to North Carolina from South Boston, Va., to spend 10 months sitting by Shane’s bedside at Duke University Medical Center in Durham. Having never heard of CDH, she immediately searched for a support group online but couldn’t find one that could answer her questions or calm her fears about her son’s diagnosis. After spending hundreds of hours in the hospital’s medical library researching CDH and only finding support from parents she met during Shane’s hospital stay, Williamson believed her mission was to create a CDH support group herself.

In 1995, she formed the charity CHERUBS — her special name for babies with CDH — in Wake Forest. The grassroots nonprofit organization is run by parents of children born with a severe birth defect. Today, it is the world’s first and largest CDH organization, with more than 3,000 members in 38 countries and all 50 states.

“I wanted to create an organization to help parents of children with CDH because I know exactly how it feels to have your dreams of delivering a healthy baby suddenly turn into your worst nightmare,” Williamson says. “I understand the emotional roller coaster that these families experience, so to be able to give them a place to turn for support is very rewarding.”

A common thread

Sadly, Shane passed away in 1999 when he was just six years old. He spent his last weeks in the hospital with a recurrent CDH and a very rare complication called a gastropleural fistula, or an opening between his stomach and his lung that caused pneumonia.

But there are CDH stories with happier outcomes. Survivor Lizz Lopez was born in 1972 in Burlington. Like Williamson, Lopez’s mom had a terrible feeling that something was wrong with her while she was pregnant. She even told her husband that they needed to start saving money for medical bills. Lopez was born blue and not breathing and was immediately rushed to Memorial Hospital at UNC, where X-rays revealed that something was not right. Surgeons weren’t quite sure how bad the situation was until they opened her up. She had her first CDH surgery at four hours old and has been fine ever since.

Modern technology certainly has made in-utero diagnosis more common. However, according to Dr. J. Duncan Phillips, surgeon-in-chief at WakeMed Children’s Hospital in Raleigh, a 2009 CDH study group registry of 65 medical centers throughout the world revealed that roughly 50 percent of parents are unaware that their baby has CDH until after he or she is born.

“If the defect is picked up by ultrasound, then the pregnant mom is usually referred to a perinatologist for high-risk pregnancy and a level 3 ultrasound is conducted,” Phillips says.

In Williamson’s case the traditional ultrasound did not pick up the defect, and Lopez was born in the early 1970s during a time when ultrasounds in physicians’ offices were uncommon.

Living with CDH

Williamson can remember vividly the day her life changed. With that one breath, a huge amount of fear and anxiety flooded in. She remembers Shane being whisked away, and the frustration of not knowing if her baby would survive.

Things change by the minute or the hour with CDH babies. Phillips recommends that parents stay calm and wait for frequent updates from their medical teams. Some babies do well, but ones that are struggling are referred to hospitals that are more equipped to handle the severity of their defects.

“Some patients may even be candidates for treatment in utero prior to delivery,” Phillips says. “There are big fetal centers across the country, including in San Francisco, Philadelphia and Cincinnati.”

To date, there is no known cause for CDH. The Internet provides parents and other concerned family members with an opportunity to do what health care providers and government agencies should be doing but often don’t: come up with support groups for other parents and family members.

Fortunately for parents-to-be or new parents who have been given a CDH diagnosis for their child, they have a place to turn. CHERUBS offers a place to get answers to their questions, talk with other parents of CDH children and learn more about some of the long-term effects from survivors.

“We are really very grateful to parents like Dawn for taking this job upon themselves,” Phillips says.

Kelly Maicon is a freelance writer based in Raleigh.